Scripture Alone!

By Scott McClare

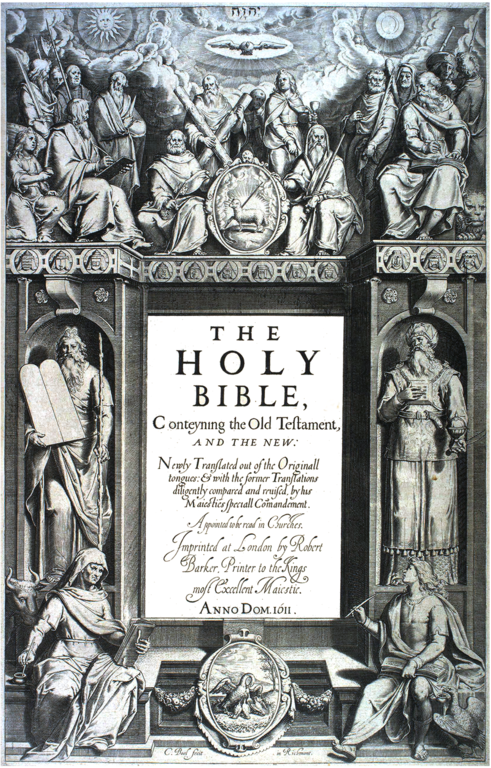

Sola Scriptura—Scripture alone—has been called the formal principle of the Reformation.[1] This is the principle that Martin Luther famously appealed to when he declared at the Diet of Worms, "Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason—I do not accept the authority of the popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other—my conscience is captive to the word of God."

As important as it is, many evangelical Christians have difficulty defining sola Scriptura, understanding what it means, or knowing how it has been derived. One high-profile convert to Roman Catholicism, Scott Hahn, says that one of the milestones on his journey to Rome was when one of his theology students asked where the Bible taught sola Scriptura, and he had no adequate answer.[2]

How, then, can we define this vital, yet misunderstood, doctrine?

The key Bible verse for sola Scriptura is 2 Timothy 3:16-17:

All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.[3]

The Apostle Paul says, first, that the Scriptures are "breathed out by God." This is a literal translation of the Greek word Paul uses, theopneustos. The Bible is, as it were, the very breath of God Himself: where the Bible speaks, He speaks. Theopneustos occurs in the Bible in this one passage. In other words, Scripture—graphe, the written Word—is said to be God-breathed, but nothing else is. The Bible is the sole God-breathed, infallible norm.

Paul goes on to say that Scripture is sufficient: by it "the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work." Here is an analogy. I am currently preparing to go to school in January. I need to purchase a number of things: a laptop computer, software, textbooks, and so forth. I can buy all these things in the college bookstore. It is sufficient to equip me for my classes. However, if I can't buy the laptop there—if they have to send me to Best Buy to get it—then they aren't sufficient. They would be incapable of fully equipping me for school.

Paul goes on to say that Scripture is sufficient: by it "the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work." Here is an analogy. I am currently preparing to go to school in January. I need to purchase a number of things: a laptop computer, software, textbooks, and so forth. I can buy all these things in the college bookstore. It is sufficient to equip me for my classes. However, if I can't buy the laptop there—if they have to send me to Best Buy to get it—then they aren't sufficient. They would be incapable of fully equipping me for school.

Similarly, the Scriptures contain "those things which are necessary to be known, believed, and observed for salvation," as the 1689 London Baptist Confession puts it.[4] If one of those necessary things was not found in the Scriptures—if I could only find it in the sacred tradition of a particular church organization—then the Scriptures would not be sufficient. They would not be capable of making me "complete, equipped for every good work." The Roman Catholic Church affirms the infallibility of the Bible, but when it says that it has been entrusted the "sacred deposit" of both Scripture and Tradition, and that only the Magisterium is capable of making them known, it denies what 2 Timothy 3:16-17 means.[5]

While this passage teaches sola Scriptura explicitly, we see it practiced implicitly by Jesus and the Apostles. Jesus rebuked the Pharisees: "You are wrong, because you know neither the Scriptures nor the power of God" (Matthew 22:29), holding them responsible for what they knew of the Scriptures; the Apostles turned to Scripture when they chose a replacement for Judas (Acts 1:20); Luke commends the Jews in Berea for their use of the Scriptures to check out what Paul taught them about Christ (Acts 17:11), among many other examples.

One Roman Catholic objection to sola Scriptura is that Scripture might be an authority, but it is not the only authority. I happen to agree; however, sola Scriptura, properly understood, does not claim that the Bible is the sole authority or the only source of truth. We do not deny that there are other authorities, such as creeds and confessions, church councils, or even pastors and teachers, who are a gift from God for the benefit of the church (Ephesians 4:11ff). However, these authorities are subordinate to the Scriptures. The Bible is not the only authority; however, it is the final authority.

Another objection is that the early church fathers didn't believe in sola Scriptura. However, we should not make the mistake of assuming that the early church was unanimous in all its beliefs and practices. Christians lived all over the known world. Each region had its own distinctive practices and traditions. Many times these were assumed to be of apostolic origin simply because they had been practised there for a long time. Because of the huge distances involved (and a lack of rapid transit and smartphones!), representatives of the whole church rarely assembled together in an ecumenical council, and only did to settle vitally important controversies.[6]

One fourth-century father, Basil of Caesarea, wrote this concerning his disputes with the Arians:

They are charging me with innovation, and base their charge on my confession of three hypostases, and blame me for asserting one Goodness, one Power, one Godhead. In this they are not wide of the truth, for I do so assert. Their complaint is that their custom does not accept this, and that Scripture does not agree. What is my reply? I do not consider it fair that the custom which obtains among them should be regarded as a law and rule of orthodoxy. If custom is to be taken in proof of what is right, then it is certainly competent for me to put forward on my side the custom which obtains here. If they reject this, we are clearly not bound to follow them. Therefore let God-inspired Scripture decide between us; and on whichever side be found doctrines in harmony with the word of God, in favour of that side will be cast the vote of truth.[7]

In other words, the Arians had their traditions, and Basil had his, and neither accepted the other's as binding. Only "God-inspired Scripture" could infallibly arbitrate between them.

Augustine, who apparently had a higher view of sacred tradition than Basil, said something similar in his dispute with the Donatists:

[L]et us not listen to "you say this, I say that" but let us listen to "the Lord says this." Certainly, there are the Lord's books, on whose authority we both agree, to which we concede, and which we serve; there we seek the Church, there we argue our case.[8]

Augustine and Basil certainly sound a lot like Martin Luther did, a millennium later! All of them recognized that human authorities and traditions were not consistent from place to place or time to time.

A third objection is that if Scripture is the sole infallible authority, then its interpretation is fallible, so only an infallible Church can infallibly interpret it.[91] How else could we decide a sincere dispute between two Christians about the meaning of a difficult passage in the Bible?

Again, this is not an argument against sola Scriptura. It only shows that people are fallible. In fact, an infallible Magisterium would be of little help. In all the centuries of its existence, the Roman Catholic Church has only supposedly interpreted a handful of passages infallibly, meaning what it has said about the vast majority of the Bible must be fallible. There is no third possibility.

A doctrine closely related to sola Scriptura is that of perspicuity: in all essential matters pertaining to salvation, the Bible speaks plainly and clearly. These subjects are "so clearly propounded and opened in some place of Scripture or other, that not only the learned, but the unlearned, in a due use of ordinary means, may attain to a sufficient understanding of them."[10] Of course, not all Scripture is equally clear and plain. As Peter wrote, some parts were hard to understand (2 Peter 3:16). What is his answer to this problem? He encourages his readers to "grow in the grace and knowledge of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ" (3:18). Peter—whom Roman Catholics claim as the first pope—does not tell them to appeal to an infallible church hierarchy. He tells them to get more understanding. When we find ourselves in an honest disagreement about the Bible, should we not prayerfully do the work it takes to bring us closer to the truth? Jesus, Peter, and the other Apostles hold us accountable for what we know of the Scriptures. It would be unwise to hand that responsibility over to someone else.

The Holy Scriptures are infallible. Human beings are not. If we are to maintain a Christian worldview and defend it before others, we need to ground our understanding on the solid rock of the Bible rather than the shifting sand of human tradition and opinion. And we need to know why, because many of those people whom our apologetics are for, find their authority in something else.

[1] A formal principle of theology is its authoritative source. Contrast this with the material principle, which is the theology's central teachings. In the Protestant tradition, the material principle is the glory of God or justification by faith alone.

[2] Scott Hahn, "The Scott Hahn Conversion Story," Catholic Education Resource Center, accessed December 2, 2015, http://www.catholiceducation.org/en/religion-and-philosophy/apologetics/the-scott-hahn-conversion-story.html.

[3] All Scripture passages are taken from the English Standard Version (ESV).

[4] London Baptist Confession of Faith [hereafter LBCF] I.7, accessed December 2, 2015, http://www.vor.org/truth/1689/1689bc01.html.

[5] Catechism of the Catholic Church 84-85 (New York: Doubleday, 1995). The Magisterium consists of "the bishops in communion with the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome."

[6] One such example was the Council of Nicaea in 325, convened to debate the teachings of Arius, of which I have written previously.

[7] Basil of Caesarea, Letter 189, New Advent, accessed December 2, 2015, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3202189.htm.

[8] Augustine, On the Unity of the Church, III.5, Christian Resources, accessed December 2, 2015, http://www.christiantruth.com/deunitate.html.

[9] "[I]t is the Magisterium which has the responsibility of guaranteeing the authenticity of interpretation. . . ." Pontifical Biblical Commission, The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church (Sherbrooke, QC: Editions Paulines, 1994), 101.

[10] LBCF I.7. By "due use of ordinary means," the authors meant such things as prayer, corporate worship, the preaching of the Word, and private and corporate study. Of course we must acknowledge the work of the Holy Spirit in aiding our understanding, as well.